So this post is my highly subjective personal point of view on contributing to and maintaining open source projects, there’s likely opinions that differ from mine. There’s a lot to the subject so I’m likely to miss something, regardless I would love to hear your feedback!

This post will be “platform” agnostic and I believe most of my reflections would apply to any OSS project, but for disclosure I’m mainly active in the .NET open source community and there’s mainly where my experiences reside from. I at times get a feeling maybe the .NET community isn’t as mature when it comes to open source, there’s a few old successful projects, but at times there’s almost a stigma of old pain present. That said I feel that’s really changed during the last couple of years, I feel there’s a bright future for .NET OSS and that the old stigma lies mainly among the ones that left the platform during it’s “dark” period — and for what I’ve seen many communities share our blessings and curses.

I’ll speak both on the role as contributor and the role of maintainer, starting with contributing. Though there’s a clear intersection with many things do apply to both.

Contributing

So maintaining open source has likely colored my perception of what’s a good contributor workflow as it’s how I wish people act and I’m trying to live by it myself.

Issue first

Before even writing the first line of code raise an issue and get buy in on your proposal from the maintainers. There’s several reasons for this, people might already be working on the issue, the issue might not be an issue or by design, but mainly just letting the community know your working on something, it gets “assigned” to you and you get implementation detail feedback early. All to reduce chance of redoing work or getting your contribution rejected. Raising an issue first is also an great way to weed out inactive or abandoned projects, if they don’t bother answer your issue chances are that they won’t review your pull request.

Contribution Guidelines

A CONTRIBUTION.md file in the root of the repository is the convention for maintainers to state the guidelines for how to contribute, stating what’s expected and required. If a CONTRIBUTION.md exists, then GitHub will presents “Please review” notice at pull request creation time, but then it’s basically too late, you could already be in “violation” and hopefully just having to go back rework things. This mainly comes down to valuing your and maintainers time, if your pull request isn’t ready don’t waste anyone's time. If it’s not ready but you need to submit it for some reason make it clear that it’s work in progress, sometimes this is totally the way to go, especially for bigger and more complex pull request where you might want feedback as you go, need testing under continuous integration etc. If a repository doesn’t already have a CONTRIBUTION.md file in-place, then I suggest you first add an issue about that, working out what maintainers expect from contributors and in that issue, and perhaps contributing guidelines could be your first contribution.

License

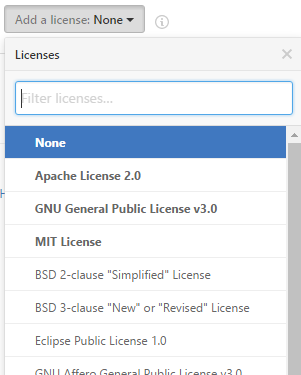

License and legals stuff might not be the first thing people think of, but be sure the code is yours to commit, that you have the right to reassign the copyright to that code, if code is used or developed at employer be sure to get the OK for it to be contributed. Even code on places like Stack Overflow could have an incompatible licence. And even if the code is under a very permissive license, please attribute the originating author — if nothing else as a thank you!

The convention for regarding licence is to have either a text file named LICENSE or could also be a markdown file named LICENSE.md. If a repository doesn’t have an LICENSE file, yet again my advise is to raise an issue and potentially let this be your first pull request.

Focus

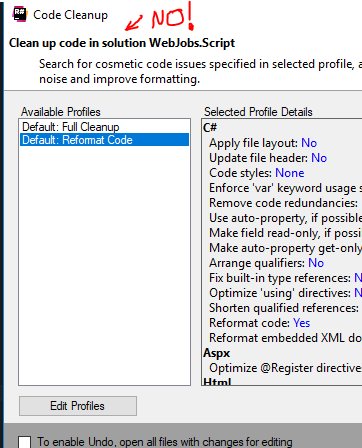

Pull request should be focused, only touch things related to your change and follow the existing coding style. Coding style changes if done should be done after buy off in a separate pull request. It all comes down to the less noise you create the easier it is to review and accept an pull request. Also especially with your first pull request it’s good if your investment isn’t too big, so the prestige is low if your proposal should get push back or be ignored by maintainers. To go to extremes, if you intent is to add just an property, don’t reformat all the code in the file, that’s a guaranteed recipe to get push back.

Tips

To not go mad execute tests and make sure they pass before you begin, then make sure they pass and that you provided coverage for new features before you send in the pull request. Even if the maintainers don’t require it keep your work in a feature branch, makes it allot easier to keep your pull request up-to-date with the upstream branch your pull request is targeting. GitHub also now allows you to enable maintainers to push changes to feature branches, which I encourage you to do, this let's maintainers if needed do tweaks before merging without you losing any attribution, especially important for repositories which have protected branches turned on, forcing pull requests to be in line with the upstream branch.

Patience

A major part of open source projects are done on a volunteer basis, on their spare time, time conflicting with things like having a family, going on vacation, hobbies etc. So don’t have the same expectations as you would have for a paid commercial software, even though you often can get excellent and quick support, don’t take it for granted as a SLA.

Maintaining

I could almost write the opposites apply here, that I’ve learned allot about maintaining by contributing, especially the social aspects of contribution. But I’ve also been fortunate to maintain projects that get contributions on a regular basis. There’s some apparent repeats from contributing but here’s my take on being a good maintainer:

Readme.md

You need one! Don’t expect people to get what you get, don’t expect people to see the brilliance of your project, you need to tell them! The convention here is to have a README.md markdown file in the root of your repository and it’ll automatically be displayed as the “landing page” of your repository. Explain the project's purpose, how to get started, any dependencies and so on. It’s your chance to sell the project.

Contribution Guidelines

You are a snowflake, or at least there’s a small chance people just by looking at your repo won’t get how you want contributions, code and tests. So having a CONTRIBUTING.md in your root project that briefely communicates to contributors how to collaborate, makes it possible for them to get and comply with your expectations.

Contributor Code of Conduct

Because common sense, ain't that common… seriously how we communicate and treat people is crucial to have diversity and make everyone feel welcome. I feel strongly about this, you don’t have to invent anything yourself the Contributor Covenant is an excellent initiative adopted by many, it has versions available as Markdown, HTML and text, they’ve also got localized versions available. The convention most use is to put a CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md file in the root of the repository. Many also link to it in their readme and contributing files.

Issue and Pull Request templates

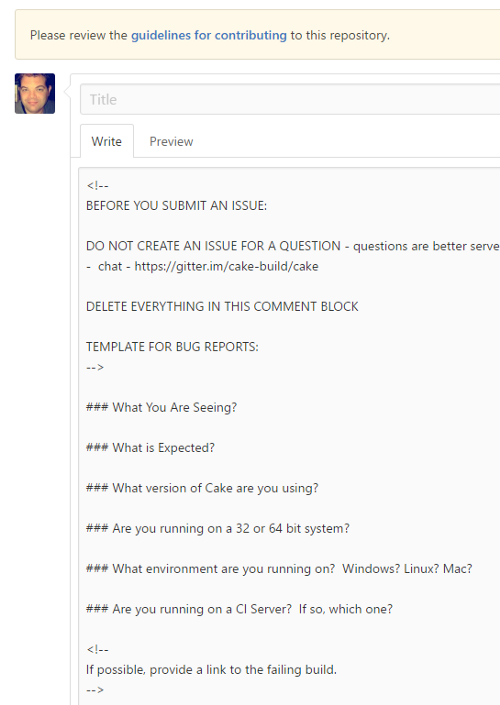

GitHub offers a great way to communicate how you want your issues and pull request raised is through issue and pull request templates.

Basically it’s either an ISSUE_TEMPLATE.md or PULL_REQUEST_TEMPLATE.md file placed in repository root or .github folder in root. These templates will then be prefilled in the comment box of an issue / pull request.

This lets you ask the questions you 90% of the time would ask anyways, questions asking gets old pretty quick. And to be fair even if they’re obvious questions to you, they might not at all be for someone new to the project.

In some cases the common questions could even lead to the issue not even being raised — often found myself that a good formulated question often results in being the answer.

Continuous Integration

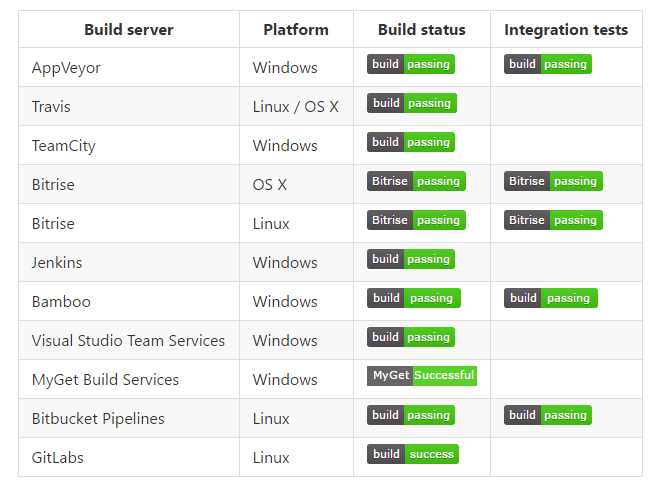

Being a maintainer of an open source build system — this indeed is something close to my heart. Software is complex, especially if you're targeting multiple platforms, automation is the only viable option to get some peace of mind that regressions are kept to a minimal.

With the Cake project people might think we’ve gone over the top building every commit that goes in on 11 different systems and various versions of Windows, Linux and MacOS…

…but it’s actually saved our bacon several times, i.e. we’ve had specific versions of Linux kernels causing issues on GitLabs, we’ve had unit tests running breaking on certain systems because certain log output been treated as service messages, we’ve had unit tests fail because test runners had smarts tied to specific build servers. Some issues been caused by the fact that some build servers are stateless, whereas some keep state and some have a hybrid approach where they have a target cache for i.e. dependencies.

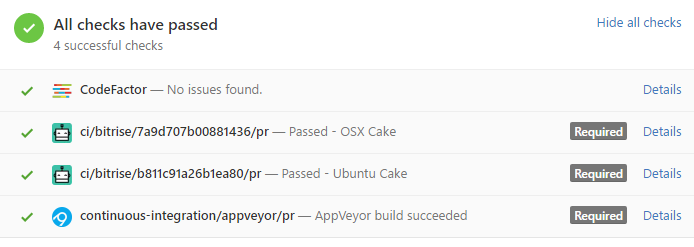

Many build services also have support for continuously building pull requests, on GitHub these are called status checks,

status checks is a great way to automatically review if the pull request is ready for review, which saves time and gives quicker feedback to the issuer. It also saves you from needing to nag, it’s harder to argue with a bot :) GitHub has an fairly easy API for status checks, so here is a perfect opportunity for you to go all devops and implement custom checks. With Cake we don’t only have checks ensuring code builds and tests pass, we also have tests in place for code style and code complexity. All this helps to keep the code in good shape, gives confidence in few regressions and speeds up the PR review process. GitHub

Keep things tidy

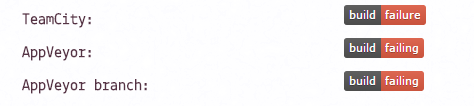

There’s somethings that really annoy me… i.e. arriving at a project and it looks like this

for me it’s a matter of good hygiene that the default branch builds and have no failing tests. Even if you are the maintainer — work in feature branches or forks. Have your build process briefly documented (even if it’s just build.sh/ps1) in the readme or link to it from the readme, preferably have an build script in place that preferably takes care of any dependencies so it’s just a matter of clone & build to get going. As a contributor it’s super frustrating to fork, start coding and not be able to build or having tests fail and realize it’s not an regression but tests was failing going into the project. Also try to stay as isolated within the repository as possible, if not please clearly notify/document, try to keep unit tests self contained as possible — try working in-memory rather on disk with files. Once had a project create thousands of files and folders in user home and temp folders —let just leave it at — I did not appreciate that. If you as you should have build scripts be sure to test them on another computer, chances are that things you have in path might not be on another, gold star if you start with an vanilla OS install and document which Debian/Chocolatey/msi packages are needed to get up and running.

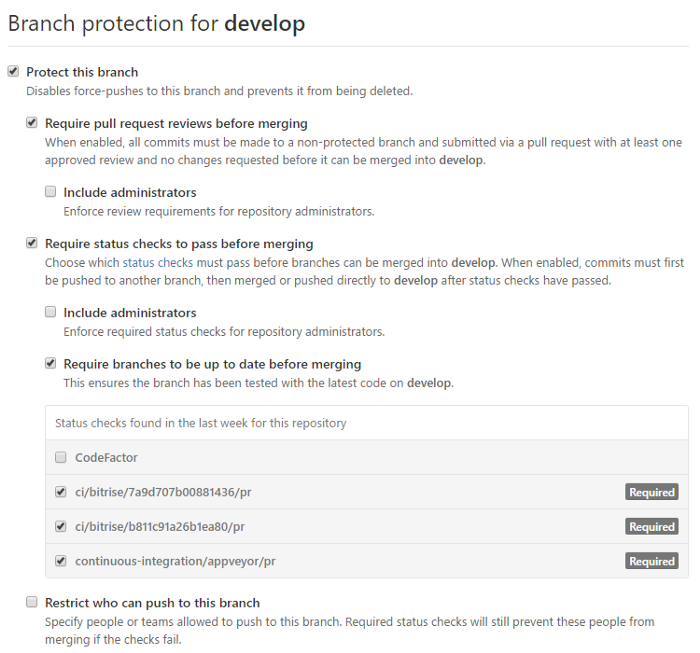

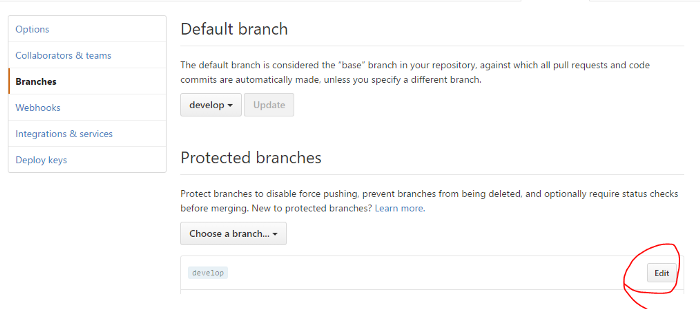

Protected Branches

GitHub offers a great way to enforce your process, that CI and status checks have passed, pull request has been reviewed by someone else than issuer, pull request hasn’t fallen behind target branch etc.

You’ll find these settings under Repo->Settings->Branches->Edit

Promises

If you can acknowledge issues and PRs quickly that’s great, but don’t promise anything too specific you can’t keep, because promises turn into expectations. What do I mean by this? Initially when an issue is raised people usually don’t expect it to be resolved within 24 hours, but if you comment on an issue like this:

I’ll look into this tonight.

then people expect you to do so, but if aren’t 100% sure that you have dedicated time “tonight” it’s really easy that life gets in the way, resulting in getting stressed for a “deadline” not met and the issuer gets disappointed, based on expectations you raised. If you instead are intentionally are a bit more vague:

I’ll look into this as soon as possible and then pingback on this issue my findings.

then if you do look and resolve it “tonight” you would have under-promised and over-delivered, and by the odd chance issuer had a more firm date in mind or have issues with that then they can reply with that feedback or take a decision to i.e. to go with a work-around.

In general try to avoid setting firm dates, for instance with a release it’s better to tie it to conditions need to be met, i.e. all issues in milestone must be closed.

Get a Team

If you are fortunate to have a project that gains some traction, then the best advice I can give is to keep an eye out for prospects to join as maintainers. Often that it can be a really active contributor that’s doing solid work or just someone you know and trust. It’s hard to give control of your creation, but the benefits for the longevity of the project and frankly your sanity is huge. Sooner or later you’ll have that pull request you need to reject, troublemaker amongst the issues or life in general just throws you a curveball — in those scenarios it’s just such a relief to have someone to privately bounce ideas with, or that just can keep merging and answering when you’re not able to.

Conclusion

It all basically comes down to communication, it’s hard! And doing it with people you’ve never met raises the bar. But the key takeaway — be civil and polite, automate as much process as possible and as with process in general you’re never done — there’s always room to iterate, refactor and continuously improve the process.

This post is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License